Georgian cuisine, wine, and nature speak the international language and require no translation—the value of these things is immediately perceptible. Unfortunately, this is hardly true of Georgian literature: the unique Georgian script was included in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2015. Georgian historical medieval literature is an important source of revealing the history of the region, but it is extremely poorly preserved.

The origins of Georgian literature date to the 4th century, when the Georgian people were converted to Christianity and a Georgian alphabet was developed. The emergence of a rich literary language and an original religious literature was simultaneous with a massive effort to translate texts from Greek, Armenian, and Syriac. Among the earliest works in Georgian is the prose Tsameba tsmidisa Shushanikisi dedoplisa (470 or later; “The Passion of Saint Queen Shushanik”), attributed to Iakob Tsurtaveli. Old Georgian ecclesiastical literature reached its acme in the 10th century with the lyrical hymns composed and collected by Ioane Minchkhi and Mikael Modrekili and with such biographies of the Church Fathers as Tskhovreba Seraapionisi (c. 910; “The Life of Serapion”) by Basil Zarzmeli and Grigol Khandztelis tskhovreba (c. 950; “Grigol of Khandzta”) by Giorgi Merchule. Chronicles—such as Moktseva Kartlisa (c. 950; “The Conversion of Georgia”) and Kartlis tskhovreba (compiled between the 10th and 13th centuries; “The Life of Kartli”)—evolved from legend to genuine historiography.

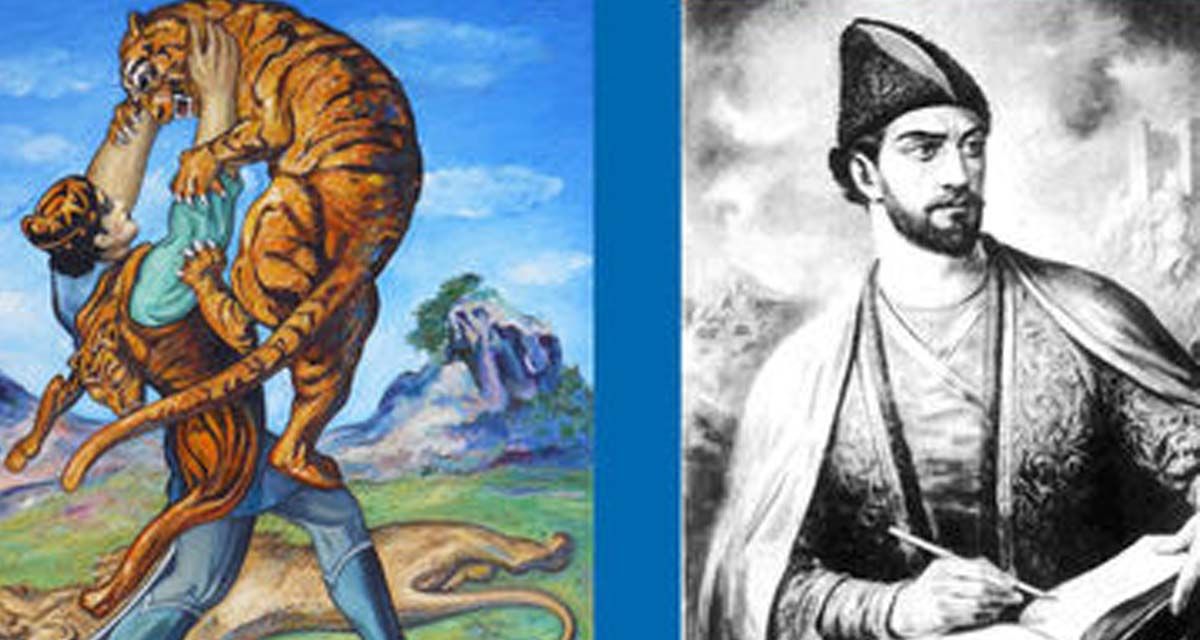

With the weakening of the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century, Georgia’s rulers achieved prosperity sufficient to allow a secular literature to develop. King David IV (the Builder) and, later, Queen Tamara, his great-granddaughter, oversaw a cultural golden age that reached from the late 11th to the early 13th century. They encouraged and commissioned works in all the arts but particularly in poetry and prose. Influenced by Persian literature—especially Ferdowsī’s Shāh-nāmeh (“Book of Kings”), an 11th-century epic—Georgian courtly romance and epic flourished. In verse, Georgia acquired its national monument, Shota Rustaveli’s extravagant but sophisticated courtly romance Vepkhvistqaosani (c. 1220; The Knight in the Panther’s Skin). It was preceded and perhaps influenced by Amiran-Darejaniani (probably c. 1050; Eng. trans. Amiran-Darejaniani), a wild prose tale of battling knights, attributed by Rustaveli to Mose Khoneli, who is otherwise unknown.

In the early 18th century, Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, supported by his pupil and nephew King Vakhtang VI, introduced modern schooling and printing to Georgia. Orbeliani also compiled the first extant Georgian dictionary and wrote a book of instructive fables, Tsigni sibrdzne-sitsruisa (c. 1700; The Book of Wisdom and Lies). Two major poets emerged in the next generation: Davit Guramishvili used colloquial language to write revealing autobiographical poetry that has a Romantic immediacy, and Besiki (pseudonym of Besarion Gabashvili) adapted conventional poetics to passionate love poetry. Both died in the 1790s while in exile.

During the 18th century, Georgia sought salvation from Ottoman and Persian rule by making an alliance with Russia. In 1801 Russia abolished the Georgian state, dethroned its kings, and made Russian the language of administration. But Russian rule was fairly bloodless and opened routes to European culture. A generation of Georgian Romantic poets was inspired by French and German literature and philosophy. Aleksandre Chavchavadze, father-in-law to Russian playwright Aleksandr Sergeyevich Griboyedov, was an original, contemplative poet; Nikoloz Baratashvili was a visionary genius comparable to the English poet John Keats.

Prose fiction, which could be sustained only by a large educated readership, was slower to develop. By the 1860s, however, fiction and nonfiction prose was flourishing. Ilia Chavchavadze and Akaki Tsereteli had immense moral and intellectual authority and measurable narrative talent, as displayed, for example, in Chavchavadze’s Katsia-adamiani? (1859–63; “Is That a Human Being?”), which attacks the degenerate gentry, and Tsereteli’s fine autobiographical Chemi tavgadasavali (1894–1909; “The Story of My Life”). Aleksandre Qazbegi was the first commercially successful prose writer in Georgia, his melodramatic fiction drawing on the legends and pagan ethos of the Caucasian highlanders. Vazha-Pshavela (pseudonym of Luka Razikashvili) is modern Georgia’s greatest genius. His finest works are tragic narrative poems (Stumar-maspindzeli [1893; “Host and Guest”], Gvelis mchameli [1901; “The Snake-Eater”]) that combine Caucasian folk myth with human tragedy. Young Georgian poets and prose writers were subsequently inspired by European Decadence and Russian Symbolism as well as by the highlanders’ folklore that imbues all Vazha-Pshavela’s language, imagery, and outlook. His greatest pupils were the dramatist and novelist Grigol Robakidze and the poet Galaktion Tabidze. Robakidze developed the themes of Vazha-Pshavela’s “The Snake-Eater” in The Snake Skin, a tale of a poet’s search for his real identity. Robakidze also led a group known as the Tsisperqnatslebi (“Blue Horns”); its best poet was Titsian Tabidze.

In the 1920s and ’30s the prose writer Mikheil Javakhishvili went on to become a great writer—produced inventive and captivating prose that often tells the story of a sympathetic doomed rogue, as in the novels Kvachi Kvachantiradze da misi tavgadasavali (1924; “Kvachi Kvachantiradze and His Adventures”) and Arsena Marabdeli (1933–36; “Arsena of Marabda”). The most enigmatic Georgian prose writer of the 20th century was Konstantine Gamsakhurdia; like Robakidze, he was influenced by German culture (especially the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche), and in his work he combined the ethos of the Austro-German poet Rainer Maria Rilke with Caucasian folk myth.

Fine lyrical poets achieved great popularity in the 1960s: Ana Kalandadze (who had been a harbinger of literary renewal in the 1940s, when her earliest work was published), Murman Lebanidze, and Mukhran Machavariani.

Chabua Amirejibi continued in the spirit of Javakhishvili’s novels centred on rogues with the magnificent Data Tutashkhia (1972) and the autobiographical Gora Mborgali (1995), while Otar Chiladze, with Gzaze erti katsi midioda (1972–73; “A Man Went Down the Road”) and Qovelman chemman mpovnelman (1976; “Everyone That Findeth Me”), began a series of lengthy atmospheric works that fuse Sumerian and Hellenic myth with the predicaments of a Georgian intellectual.